Why we need soft textures right now

Fabric art and interiors are helping to make home the ultimate comfort zone. Dominic Lutyens talks to the creators of the cosy, tactile aesthetic.

A desire to soften the hard lines of traditionally boxy rooms is long-established. Some 20 years ago, the return of wallpaper took us by surprise, though now we take it for granted. Designer Deborah Bowness was at the forefront of this with her witty, pretty screenprinted trompe l’oeil designs, including tea dresses hung on bedroom walls, their fabrics picked out in sugary colours. For some time, paint colours have erred towards moodier, sludgier hues, such as navy or moss green, reflecting a yearning for cosier spaces.

Now a burgeoning trend for textiles in the home is taking things further – not just softening a room’s hard parameters but luxuriously cushioning and padding walls, floors and furniture. A growing band of designers are creating wall-hung textiles, ranging from delicate silk wallpapers to more textured, three-dimensional wall-hangings. It’s hard to know if these designers, who deploy old and new techniques, from embroidery to digital technology, are fuelling a demand for these pieces or meeting it.

Emma Lewis

Emma LewisDesigners today often plump for natural, plant-based fibres, such as bamboo, jute, coconut waste and even vegetable waste, which enhance the warm quality of textiles. Different materials and techniques result in variations of texture and finishes, some matt, others glossy. Sustainable materials and methods of dyeing are also increasingly deployed, reflecting a greater responsibility towards the environment.

As opposed to rigid, unalterable fixtures, textiles can be easily repositioned, making them informal and adaptable, and they can be layered for extra comfort. Inevitably, perhaps, lockdown saw rising sales of throws, cushions and rugs, according to Charlotte Bastholm Skjold, senior vice president of products at Kvadrat, the Danish upholstery fabric company. “In the first few months of the pandemic, our range of cushions, throws and rugs were very popular,” she says. “They could be bought online and added to people’s homes easily.”

A glut of digital technology in our lives is also stoking the trend, she adds: “Textiles soften our environments, in which technology is so dominant. When we spend so much time staring at screens, you’re only experiencing one of your senses – the visual – but fabrics are tactile and engage the sense of touch. They give a space a human quality.”

Kvadrat

KvadratArguably Kvadrat pioneered flexible ways to subdivide spaces informally using textiles: in 2008, it introduced Clouds, designed by French designers, the Bouroullec brothers. The easy-to-assemble modular design comprises textile tiles manually joined using elastic bands. These can form free-standing, sound-absorbing screens or can be ceiling or wall-hung. “Clouds is a tactile element that creates intimate zones in spaces,” says Bastholm Skjold.

The appeal of textiles in homes mainly harks back to medieval times (although earlier examples existed in Ancient Greece in the Third Century BC). The word tapestry derives from the French verb, tapisser, meaning ‘to cover with heavy fabric, to carpet’. Some factors that made tapestries sought-after at the time explain the appeal of textiles today: aristocrats of yore liked their portability – they could be rolled up and moved from one residence to another – and tapestries helped insulate French châteaux, just as textiles today make interiors warmer.

“There’s a great history of textiles on walls dating from medieval times in Europe as well as suzanis and kilims hung in tents in the Middle East and Asia Minor,” says London-based textile artist Alan Oliver, who makes handwoven, hand-dyed wall-hangings and rugs. “Textiles provide something you don’t quite get from paints and wallpaper – feelings of comfort and safety. They give psychological and physical warmth and speak to our desire to nest. Another appealing aspect of textiles is their perceived impermanence, which allows people to make bolder choices than with a painted artwork or piece of furniture.”

Claire Coles

Claire ColesOliver’s work includes his Rebar wall-hanging with an abstract design in a dusky pink – an entirely organic effect resulting from dyeing the yarn using the skins and pits of discarded avocadoes (collected from local cafés). “The dye is high in tannic acid, a safe alternative to the toxic mordants normally used to fix dyes to fabric and make them more colour-fast.”

Sarah Campbell, a British doyenne of textile design, believes textiles enliven spaces. “Textiles as curtains and on sofas reflect light,” says Campbell who, with her late sister Susan Collier, created many classic fabrics based on hand-painted designs for Liberty and Terence Conran’s Habitat chain in the 1970s. They were particularly influenced by the colour-saturated work of artists Sonia Delaunay and Raoul Dufy. “Textiles have a softness. Printed textiles indicate that a human being has been at work making a pattern – and allow you to see the world through another’s eyes.” Campbell is showing new hand-painted and printed pieces, including cushions and wall art, at Anthropologie’s London King’s Road store during London Craft Week (LCW) and beyond.

Anthropologie

AnthropologieA younger generation of textile designers is also showcasing work during LCW, which is on until 10 October, suggesting a renewed interest in – and market for – this craft, in particular for wall-hangings. “Textiles are in demand because of the popularity of crafts,” says Oliver. “Ceramics have already been elevated to the point of high art. Some craft pottery is becoming inaccessible in terms of price. We are now looking at other areas of craft instead – and textiles are filling that gap.”

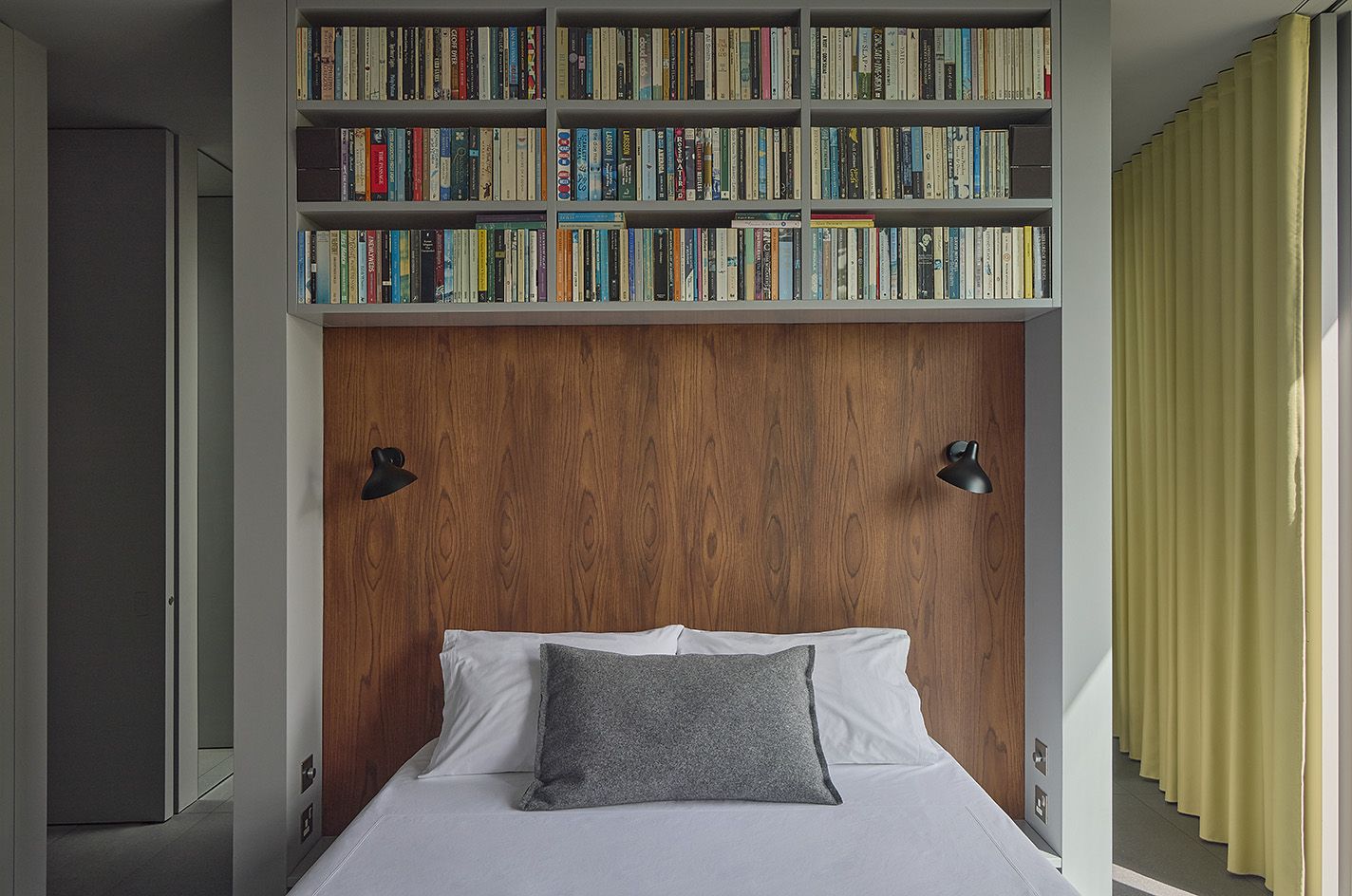

Singaporean weaver Tiffany Loy, a student at the Royal College of Art, is showing her site-specific woven column, called Weaverly Way, in collaboration with British weaving brand Gainsborough at the CitizenM hotel in London’s Bankside. This sculptural piece has an unexpectedly 3D surface. “It’s almost as though one were seeing a flat textile through a magnifying glass, which would blow up the scale of the woven threads,” she explains. “Key advantages of textiles include their translucency and ability to divide up rooms using non-permanent boundaries that don’t shrink a space. They also contribute hugely to sound absorption – there’s nothing more annoying than an echoey room.”

Emma Lewis

Emma LewisMeanwhile, another LCW participant, Ekta Kaul, creates bespoke, hand-embroidered maps. “My map commissions take inspiration from the history, architecture and more personal narratives of a place,” she says. She believes an appreciation of large-scale textiles has been partly triggered by Tate Modern’s show on textile artist Anni Albers and by quilts created by women at the African-American hamlet of Gee’s Bend in Alabama in the US, recently showcased at the exhibition We Will Walk – Art and Resistance in the American South, held at the gallery Turner Contemporary in Margate.

Claire Coles, who is showing her work at Future Icons, an exhibition at Burlington Arcade during LCW, was approached by interior designer Pip Isherwood to create a silk wallpaper for a home in west London. It features appliquéd floral motifs made of leather, suede and silk, embroidered into place in a freeform way. “I want to add depth to my wallpapers as if the motifs are coming to life,” says Coles. “My clients are looking to add texture in their homes in a new way. They’re less keen on repeat pattern wallpapers and are looking for alternative media.”

Another strand of the trend is a desire for rugged, raw-looking textures – a good example being the large-scale tapestries of duo Crossing Threads, set up by Australian sisters Lauren and Kass Hernandez. They often knot the materials they use – these include coconut husk, bamboo, jute and discarded denim – to give their pieces greater depth.

Crossing Threads will showcase their work during LCW via a new, virtual initiative called Create Day, to be held on 10 October. This will give an idea of the global reach of textile art, allowing viewers to see the work of designers all over the world, and learn about their skills via live-streamed studio tours and tutorials.

Crossing Threads

Crossing ThreadsMeanwhile Irish textile designer Aiveen Daly, who will be giving a talk during LCW, creates huge panels upholstered in fabrics of soothing monochrome colours, such as white and oyster grey. One of the most monumental of these is her piece Sea Foam, which she describes as “a quiet evocation of the rolling ocean”. It is constructed from hundreds of hand-cut, layered pieces of suede. “In a world full of anxieties, our homes are our sanctuaries like never before,” she says. “Knowing the many hours that have gone into making this work hopefully brings the viewer a sense of peace.”

link